|

This feature appears in Auto Italia - Issue 111

- Oct/Nov

2005 |

|

|

Lamborghini

watchers will know that 2005 is the 40th anniversary of the

world’s most beautiful car – the Lamborghini Miura. A normal

celebration is simply not enough for this icon of icons so

the 40th anniversary will span 2005 and 2006, because in

autumn 1965 at the Turin Motor Show, the show-stopper on the

Lamborghini stand was bereft of body. It was just a rolling

chassis with a spectacular mid-mounted transverse V12. Not

only did it not have a bodyshell but no one had even been

commissioned to design one. Nevertheless, the orders flooded

in, so boss Ferruccio Lamborghini handed the design duty to

Bertone. As soon as the Turin Show closed, Bertone got to

work on his new commission. The head of design and

brainchild of the Miura was an astonishingly young

22-year-old Marcello Gandini. After a winter of frantic

work, the March 1966 Geneva Motor Show saw the presentation

of the first real Miura and the immortality of Gandini.

The Miura’s

chassis is a fabricated steel monocoque with hinged front

and rear ends in aluminium, the huge clamshells allowing

unrivalled access to the car’s components. The engine and

transmission unit comprise one single casting which is

mounted transversely between the driver and the rear wheels,

giving a low polar moment of inertia. Centre of gravity is

also low as the gearbox and differential unit nestle behind

the engine rather than underneath it. Suspension all round

is by double wishbone, steering is non-assisted rack and

pinion and brakes are non-servo discs all round – all very

racy, yet with generous luggage capacity and way ahead of

the 1960s opposition.

Miura production

ran from 1966-1973 and saw three distinct model types: P400,

P400S and P400SV. The original 1966 Miura was a rush job and

there was no time for R&D, so each model was an improvement

but some upgrades were introduced mid-series. There were

also a few one-offs like the 1968 Miura Roadster and the

1970 Miura Jota. Ferruccio

Lamborghini permitted test driver Bob Wallace (who wanted

Lamborghini to go racing) to build the Jota – a semi-race

special. This kept Wallace busy and the snorting Jota became

a useful tool for frightening journalists. The original Jota

was totally destroyed in a high-speed crash but Lamborghini

expert Piet Pulford has built a replica of that famous car.

On seeing the original Jota, some Miura owners requested

Jota-esque modifications to their Miuras, calling them SVJs.

Ferruccio was a man on a mission. His feud with Enzo Ferrari

meant that he would not rest until he had built a better car

than his rival. You could justifiably argue that Lamborghini

succeeded with the 350GT, 400GT, and the Islero. With the

Miura there was no doubt: Lamborghini had overwhelmed

Ferrari – the bull gored the horse.

In total, 760

Miuras were built with a great many receiving upgrades. In

their heyday, Miuras had a high attrition rate and, of those

760 cars, fewer than half that number exist today. In the

Miura market, the later the car, the better, with the SV

being the most sought-after. Prices have risen rapidly and

are tipped to join the best from Maranello in the automotive

stratosphere. In the USA, good SVs have already changed

hands for over half a million dollars.

The difference

between the P400 and the ‘S’ is subtle, while the SV is

radically different. That first chassis presented at the

1965 Turin Show was a gorgeous mass of drilled metal. As the

years progressed, so the holes disappeared. The metal also

got thicker to improve the torsional rigidity of the early

cars. Consequently, each model got heavier and required more

power. The SV’s spec includes more power, a stronger

chassis, ventilated discs (introduced mid-S), different

lights, and different front end. New wide-track rear

suspension means a wider rear body, wider wheels and tyres

and more. The rear wishbones and their pick-up points were

redesigned in order to prevent rear wheel steering inputs

which accompanied suspension travel on the pre-’71 cars.

Mid-way through the SV series, the shared oil system for the

engine and transmission was abandoned for split-sump. This

separates the oil systems, prolonging the life of both

engine and gearbox, as well as enabling appropriate oils for

each.

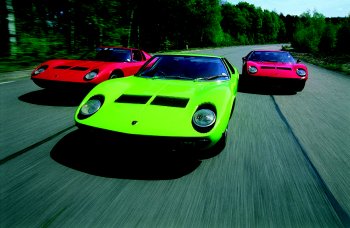

Driving a Miura

is something you don’t forget. Simply walking up to the car

brings on excitement. With the roof at waist level

(42in/1.050m) it feels much like getting into a racing car.

But unlike a racing car, ground clearance is good enough to

cope with real-world driving. As the three Miuras were let

loose on our test track, it reminded me that I must get to

the world’s wildest party at Pamplona for the running of the

bulls.

The P400

With three

beasties ready to run, let’s go in time-order with the

oldest bull first, the P400. This 1967 car is owned by Colin

Gilmore-Merchant and is a low-mileage, right-hand drive,

unrestored example. It was delivered to our test track by

Lamborghini and Ferrari specialist Colin Clarke. As you drop

down into the seat, you immediately inhale that Lamborghini

smell. This car feels soft, warm and homely, like a

favourite old jumper. The sitting position is laughable but

you quickly forget about it. The steering wheel is too far

away and set at such an angle that you could never reach the

top of the wheel without leaning forward. This is

exacerbated by the laid-back seat angle which is essential

if you want your head to clear the low roof. The Miura’s

beautiful proportions mean compromises. The pedals are too

close necessitating a splayed-leg attitude. If they had made

the sitting position more upright and raised the roof; if

they had shifted the pedals (and thereby the front wheels)

further forward, the Miura wouldn’t be the Miura.

Ignition on.

Wait for the fuel pump to settle down. Prime the 12 chokes

with a couple of dabs on the right pedal (no choke is fitted

to any Miura) and the 12 cylinders whoop and fall to a

smooth idle. Keeping the bank of Webers in tune is not the

nightmare that folklore would have you believe. Down the

not-too-heavy clutch pedal, slot the metal-gated lever into

the conventional position for first gear, and away we go.

Power is slightly less but delivery is more linear than with

later Miuras. The P400 does not have that all-or-nothing

feeling each side of 5000rpm.

|

|

|

In their heyday, Lamborghini Miuras had a high

attrition rate and, of those 760 cars, fewer than

half that number still exist |

|

|

|

Lamborghini watchers will know that 2005 is the 40th

anniversary of the world’s most

beautiful car – the Miura |

|

|

|

|

Lamborghini Miura production ran from 1966 to 1973

and saw three distinct model types built: P400,

P400S and P400SV |

|

|

|

The chassis is a fabricated steel monocoque with

hinged front and rear ends in aluminium, the huge

clamshells allowing for unrivalled

access to the Miura’s

components |

|

|

Despite the low

mileage the rear springs have suffered by supporting 60% of

the P400’s mass for nearly 40 years. Accelerative squat

drags the tail even lower as the nose rises. With this

set-up and a high air-speed, the inside of this Miura would

be a scary place to be. At lower speeds the ride is quiet

and comfy. Roll is noticeable but the suspension element in

the high-profile narrow tyres gives the P400 a fine steering

and ride quality long gone in more modern machines. It’s

great to drive a Miura in its pure original form. That it is

not as fast as the later cars is largely irrelevant as a

Miura is an art form.

The P400S

The middle-aged

bull in our triple test is perfectly matured. This very

green Miura S is now owned by Henry Weitzmann. This is the

famous ‘Twiggy Car’ that we first tested back in issue 18

(Jan/Feb 1998). The icon supermodel in the icon supercar;

something yet to be bettered. Originally a 1968 white P400,

like many Miuras this one has been upgraded. In this case a

factory upgrade in 1970 from P400 to P400S. Then in 1990 the

car was in a garage fire and was returned to the factory for

another rebuild. Henry has owned the car since 1991 and he

emphasises that it is not for sale. Miura ‘S’ upgrades include

chrome window trims, electric windows, a new switch pod in

the roof lining and the ‘S’ badge. Under the skin an ‘S’ has

a stiffer chassis and a more powerful motor. Visually, an ‘S’

is close to its predecessor, the P400, but for straightline

speed an ‘S’ is up there with an SV.

The green car

feels slightly more highly strung than the P400. The ride is

more taut and there is busy-ness from the engine. The extra

20bhp comes at the top end by stretching the red-line to

nearly 8000rpm. Even today, 40 years later, a 4-litre

production engine running at 8000rpm is quite something.

With revs comes power and speed. However, contact with your

passenger is now by SHOUTING. Interior decibels are

surprisingly low for normal town driving or even a legal

motorway jaunt, but if you want to be bad in any Miura you

will need a LOUD VOICE. Heat insulation is good, another

common Miura misconception. Less heat enters the Miura’s

cabin from mechanical components than with a front-engined

car. The main heat source is from the greenhouse effect of

the huge windscreen relative to the small cockpit volume.

Ride is comfy.

Handling is very good – to a point. Push too hard and the

Miura S will complain with roll angles, jaw, squat and dive.

The grippier the tyres, the higher the g and the greater the

jaunty cornering angles. Lift-off oversteer is here in great

quantities, requiring the driver to unwind the steering

should he/she come off the power while cornering hard. Power

delivery is superb. The Miura will pull happily from 1000rpm

round to 8000rpm, although proper power comes in at above

5000rpm.

The P400 SV

Finally, the

young bull – fighting fit and recently back from

international hillclimbs, race circuits and road rallies.

This restoration of this Miura was featured in Auto Italia

issue 106 (May-June 2005). This is a 1970 car totally

rebuilt and upgraded to SV spec. Not an easy task as just

about everything had to be changed. Let’s take my own SV for

a drive. The engine starts with an explosion of revs and

just as quickly settles down to smooth tickover. Lamborghini

engines are much quieter than those from their red rival

just down the road at Maranello.

Minute changes

to the seat angle and steering column make a big improvement

to the sitting position. Despite the gearchange shaft

passing in a straight line through the engine’s sump and

directly into the gearbox, the gearshift on any Miura

requires effort. The clutch is surprisingly light for the

period while the unassisted steering has perfect feel. It is

a little low-geared for parking but the faster you go, the

better it gets. After its restoration, the Miura’s first run

was at Monza and the handling was much better than I could

ever have imagined in a 35-year-old car. With its much wider

rubber, traction and grip are tenacious. Chassis

communication with the driver is enormous, while the

long-travel unassisted brakes do their job well enough. With

their transverse sumps, all Miuras can experience oil surge

in race conditions but not on the road. While an SV is

easily the quickest of the trio, using the SV as a racing

car means cornering at high g with one eye on the oil

pressure gauge. A dry-sump system or an acu-sump would be a

good mod for race-track use.

What makes the

SV so quick is its ability to carry far more speed through a

corner than a P400 or an ‘S’. Power delivery is innocent

enough up to 3000rpm. From 5000-8000 the Miura is truly

spectacular. High-speed Miura nose-lift is dependent on the

aerodynamic angle of attack (or rake). It only happens on

Miuras with tired rear springs. Further jacked-up by its

taller rear tyres, this Miura SV is rock steady at huge

speeds. The top-end power rush is accompanied by a crescendo

of noise. Some SVs were offered with open trumpets, and that

is what we have here. So from 2500rpm you hear that

beautiful induction noise of a bygone era. The SV will reach

60mph in first gear, making it tricky to get off the line

quickly. Second gear will see you banned from driving in

many countries, at 87mph. Third gear is good for 122mph.

Fourth gear, and you pass all the German supercars

restricted to 155mph. In fifth gear, 180mph is all yours.

If

that doesn’t irritate the Health and Safety Police, here is

a statistic. Since 1920, only 14 people have been killed at

the San Fermin Pamplona Bull Run and only a few hundred

injured. Next year’s runs are at 08.00hrs every day from

7th-14th July. See you there.

Test by Roberto Giordanelli / Photography

by Michael Ward

|

|

This feature appears in Auto Italia, Issue 111,

Sep-Oct 2005. Highlights of this month's issue

of the world's leading Italian car magazine, now

on sale, includes a Ferrari four-seater triple

test, the Maserati GranSport on track, story of

the Alfa Romeo 33/3, and the UK launch of the

Fiat Croma. Call

+44 (0) 1858 438817 for back issues and subscriptions. |

|

|

website:

www.auto-italia.co.uk |

|

|

|

|

![]()

![]()