|

Lancia, one

of the most famous and evocative of all the major automotive

brand names, was founded exactly 100 years ago. To

celebrate this milestone Italiaspeed is presenting an

exclusive 15 part history of Lancia.

For the first

fifteen-odd years of the company’s existence, Lancia had

manufactured cars which were good performers, practical and

lightweight, with a number of technical innovations. But in

the grand scheme of things, each was a stepping stone to the

model with which Lancia would truly make his name. Developed

and on the road in 1921, shown to the public at the Paris

Salon in 1922, in production by 1923; with the Lambda,

Lancia pulled together a great number of influential ideas

in a single car, and although none was entirely new, their

combination and execution in the Lambda immediately marked

it as a great leap forward. The biggest single innovation,

and one which instigated a revolution in car design, was the

adoption of a load-bearing body and the deletion of the

separate chassis. Another first was the use of independent

front suspension, while the ‘Tipo 67’ V4 engine, designed by

Ingegneres Rocco, Cantarini and Quarello, was also highly

advanced. An unusually short engine thanks to its layout,

the Tipo 67 employed a cast-aluminium engine block,

aluminium pistons, a 13° V-angle and overhead camshafts,

resulting in an output of 49 bhp at an unusually high 3250

rpm.

It is worth

pausing for a moment to explore the inspiration for the

Lambda’s two most important innovations. Although the

execution of a unitary chassis (where the chassis frame and

body frame were fabricated in steel to form a single unit)

was revolutionary in an automotive context, it was not

unprecedented in other areas of industrial design. Legend

has it that one day, Vincenzo Lancia found himself on board

a ship travelling to the U.S. in an unforgiving sea, and

watching the ship’s hull battling against the conditions

inspired him to develop a car with a unitary body – but this

account remains unverified.

It is however

true that the Lambda’s independent front suspension owes its

origins to Signor Lancia. As Paul Vellacott has observed,

“Lancia was well aware of the importance of minimising

unsprung weight and used pressed steel ‘U’ section front

axles, rather than heavier cast steel, on models up to the

1919 Kappa. Following an accident caused by a broken front

axle on a Kappa, Lancia realised that an independent front

suspension would remove the risk of broken axles and improve

handling by reducing unsprung weight.

“Having

identified a solution to the problem, Vincenzo Lancia did

not slave over a drawing board to refine the solution, but

handed the challenge over to his design engineers, the most

outstanding of whom was, undoubtedly, Battista Falchetto.

The story of how Falchetto, on being asked by Vincenzo

Lancia to come up with an independent front suspension

solution to remove the hazard he had experienced with the

Kappa’s broken front axle, is now part of Lancia lore.

Falchetto worked well into the early hours of the next

morning to produce sketch drawings of 14 possible

independent front suspension (IFS) designs. That his 1921

sketches included virtually every type of IFS introduced by

other car manufacturers during the next thirty years is

quite remarkable.” The sliding pillar design eventually

chosen was highly significant, for derivations of the type

would underpin the front of every new Lancia from then on,

up to the 1953 Appia.

The Lambda was

not just a modern car for its time – many of the solutions

it pioneered (such as a remote central gearchange,

integrated luggage boot and transmission tunnel) would find

themselves in use well after the Second World War. Speak to

Lambda owners today and apart from unstinting devotion to,

and praise for, their cars, there is one remark in

particular which comes through – that they drive almost like

modern cars, a world away from other cars of equivalent

vintage. With their long, low-slung appearance, they

certainly looked different: according to Penny Sparke, the

launch of the Lambda meant that, “for the first time, a car

could really be thought of and conceived from the outset, as

a single visual entity.”

The Lambda was

in planning for some time, with the original patent for a

‘frameless car’ filed on New Year’s Eve, 1918. An unproven

idea, it was put on the backburner for the next couple of

years as Lancia pursued development of his new V12, but with

these plans falling through, attention focused once again on

the design in the patent as the way forward, with the

go-ahead given in March 1921. One area of dissent in the

development of the car was over the issue of brakes, with

Lancia for a long time remaining sceptical of Falchetto’s

belief in four-wheel brakes, believing that rear brakes were

entirely adequate for the car. It was fortunate that

Falchetto managed to convince Lancia after a test run in a

car equipped only with front brakes, for as Trow notes,

“Lambda braking proved to be one of the features that deeply

impressed contemporary commentators.”

Throughout its

nine-year life, the Lambda underwent an extensive series of

evolutions. Briefly, the original specification saw a top

speed of between 70 and 75 mph, with a touring consumption

figure of around 26 mpg. These first cars were almost all

bodied in-house by Lancia, the new load-bearing body

reducing the scope for the coachbuilders, although a few did

make some attempts. The first four series saw small

improvements such as new pistons, different windscreen

designs and a change in supplier of the electrical system

(from Bosch to Marelli). The fifth series saw the adoption

of a four-speed gearbox to replace the previous

three-speeder, whilst the sixth series used a wheelbase

stretched by 320mm and was also produced as a chassis for

the coachbuilders. In 1926, the seventh series saw an

enlarged capacity engine (up to 2370cc) producing another 10

bhp, and was produced with both the longer and shorter

wheelbases, a feature also used in the following eighth

series (1928-1929). The latter also received an even larger

and more powerful engine (2570cc) with a further 10 bhp, now

achieved at 3500 rpm, to offset the ever-increasing

weight. By 1931 and the series 9, the Lambda had racked up

production of nearly 13,000 units, easily making it Lancia’s

best-selling model thus far. Throughout this period, the

company itself would also undergo a considerable shakeup,

with Fogolin resigning in 1921 and the rest of the firm’s

founding members (Rocco, Cantarini and Zeppegno) all

departing some time afterwards.

Thanks to their

outstanding handling and braking performance, Lambdas were

also a natural choice for competition purposes. They were

successfully utilised extensively in motorsport in various

guises, mostly by private entries, albeit supported by the

factory. Officially, the factory was uninterested in motor

racing, but Vincenzo Lancia never truly lost the racing bug

from his youth, and a 2.5-litre model was prepared by the

factory for the 1928 Mille Miglia. Despite lacking

performance on paper compared with the supercharged

1.5-litre Alfa Romeo Super Sport of Campari and Ramponi,

Gismondi was able to keep in touch as a result of the

Lambda’s superior handling, only retiring from second place

in the final leg when the engine dropped a valve.

The 1930s and

new challenges

A couple of

years prior to the Lambda ceasing production, in 1929, the

rather more conventional Dilambda had been introduced to the

market. Despite its name, this was not a replacement for the

Lambda, but a far bigger model, aimed at a different type of

customer – Lancia’s first true luxury car. In fact, it was

born as a project for the U.S. market and displayed at the

New York Motor Show as early as 1927, complete with plans to

manufacture there, but when the venture collapsed (with no

less than a serious threat on Vincenzo’s life), the car was

modified for the European market and eventually went into

production in 1929. Although it included innovative

features, such as a structural fuel tank, independent front

suspension similar in design to the Lambda, and was one of

the first cars to be fitted with a hypoid bevel, the

Dilambda returned to a separate chassis construction to

satisfy the demands of the coachbuilding industry, who would

be integral to providing a choice of bodies, as would be

expected by the buyer of such a car. Typically, customers

had a choice between a four-door, four-seat saloon, a

two-door ‘coupe de ville’, and a two-door cabriolet. Amongst

others, the Dilambda is notable for providing the base for

the first official Pinin Farina special. Lancia and Farina

were good friends and the former was crucial to persuading

Farina to branch out on his own by providing commissions.

The Dilambda was

a large car, the finished vehicle rarely weighing less than

two tonnes, and was built in correspondingly small numbers.

The total production was just under 1700 cars, with the

majority built between 1929 and 1932, although it remained

available to special order for a few more years

afterwards. It was propelled quite adequately for its

purpose by a superb new 100 bhp 4-litre V8 engine, developed

from the Trikappa’s motor but in actuality a quite different

engine, with a V-angle of 24°, pushrod-operated valves (the

first Lancia V engine with this valvegear arrangement) and

one-piece casting of the iron cylinder block.

The extent of

the Lambda’s advancement had made it the car of choice for

the discerning motorists of Europe – a point emphasised by

the fact that Lancia sold cars via reputation rather than

advertising. Moreover, according to Automotive News,

“Lancia (had) gained economies of scale by using the most

sophisticated tooling available. The result was that his

company could produce more than 4,000 units of his high-end

models a year by the 1930s”, while continued investment in

manufacturing methods allowed low-volume production of

improved models, such as the Astura and Artena, which would

debut in 1931 and herald a new era for the company.

With the

Dilambda meeting the demand for a large vehicle, Lancia went

about developing a replacement for the Lambda, to be

available both as a base model and a more luxurious model,

sharing their basic layout. The result was, respectively,

the Artena and the Astura. The resulting common chassis drew

heavily on the design of the preceding Lambda and Dilambda,

albeit with a sensible dose of cost-saving measures, with

the front and rear suspension also following the same basic

layout as those models.

For the Artena

it was decided to retain the well-tried narrow-angle V4

layout, but while it has been described as a much-developed

version of the Lambda’s V4 with numerous major modifications

(such as the adoption of a chain drive for the camshaft),

the changes were so extensive it could just about be called

an all-new engine. Whilst an overhead camshaft layout

remained, an iron block was substituted in favour of the

Lambda’s alloy specification, with the V-angle set at

17°. Slightly under two litres in capacity, a significant

innovation was its mounting via silentblocks, which

drastically reduced the vibrations passed into the

chassis. The Astura, on the other hand, got a simplified and

reduced-capacity version of the existing V8. Measuring 2.6

litres in capacity and developing 73 bhp at 4000 rpm, the

new V8 was essentially quite similar in concept to the

Artena’s V4; clearly with eight cylinders and with a

slightly expanded V-angle (19°), but much the same in basic

design and layout.

The Astura,

writes Wim Oude Weernink, was, “not a Lancia technical

tour de force with regard to chassis design,

(but)...must nevertheless be considered as one of the best

pre-war Lancias from the points of view of quality,

durability and practicality.” Even if they did not display

the innovation of the Lambda, the Astura and Artena were

fine-handling cars in the by-now Lancia tradition, with

their compact engines sited low-down in the chassis, precise

steering and well-developed front suspension allowing them

to realise Lancia’s mantra that they should be able to

maintain, “a high average speed under average conditions”.

|

|

|

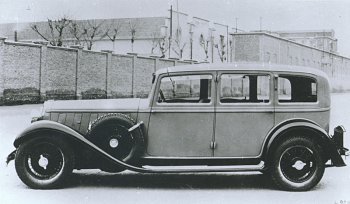

The Dilambda

was a large car, the finished vehicle rarely

weighing less than two tonnes, and was built in

correspondingly small numbers. The total production

was just under 1700 cars, with the majority built

between 1929 and 1932. |

|

|

|

For the Artena

it was decided to retain the well-tried narrow-angle

V4 layout, but while it has been described as a

much-developed version of the Lambda’s V4 with

numerous major modifications (such as the adoption

of a chain drive for the camshaft), the changes were

so extensive it could just about be called an

all-new engine. |

|

|

|

The Astura,

writes Wim Oude Weernink, was, “not a Lancia technical 'tour de force' with regard to chassis design,

(but)...must nevertheless be considered as one of the best

pre-war Lancias from the points of view of quality,

durability and practicality.” |

|

|

|

The first ‘compact’ Lancia designed to be produced

in large volumes, the Augusta was first shown to the

public in 1932, with production beginning in 1933

and a chassis version also produced for the

coachbuilders from 1934 onwards. |

|

|

|

|

Developed and on the road in 1921, shown to the

public at the Paris Salon in 1922, in production by

1923; with the Lambda, Lancia pulled together a

great number of influential ideas in a single car,

and although none was entirely new, their

combination and execution in the Lambda immediately

marked it as a great leap forward. |

|

|

|

The biggest single innovation of the Lambda, and one

which instigated a revolution in car design, was the

adoption of a load-bearing body and the deletion of

the separate chassis. |

|

|

|

Tragically, Vincenzo Lancia would not live to see

the Aprilia go into production and receive the

plaudits it richly deserved. It was, perhaps, the

strain of running what had become a large

organisation which was taking its toll. |

|

|

|

Despite its diminutive size, the Augusta was a particular favourite with

racing drivers of the era, with Tazio Nuvolari, Luigi

Fagioli, Antonio Brivio, Achille Varzi and Rene Dreyfus all

espousing the qualities of the ‘littlest Lancia’. |

|

|

In particular, early Asturas were regarded as

very sporting cars, especially when fitted with low, wide

custom bodies by the likes of Pinin Farina, Touring, Viotti

and Castagna. It was potential realised to an extent in

competition, with Pinaduca and Nardelli claiming victory in

the 1934 Circuit of Italy, a grueling trial of some 5654km

over which their Astura averaged 85km/h. Trow notes, “it

(was) to the Lancia’s credit that Pintaduca and Nardelli

beat the new 6C 2300 Alfa Romeo of Scuderia Ferrari, the

Alfa works team, by over three minutes,” while third place

was claimed by another Astura, piloted by another who would

go on to greater things – Giuseppe Farina.

However, towards

the end of its life, the Astura would increasingly evolve

into a large tourer, in much the same way as the Lambda had

done, to suit the demands of the political climate in Italy

at the time. Whilst the Artena became more utilitarian given

the poor economic conditions at the time and the limited

purchasing power of most Italians, the Astura took over as

the top-of-the-range Lancia and became more luxurious after

the cessation of production of the Dilambda in 1938. In 1934

its engine was bored out to 3 litres, raising output to 82

bhp, while a variety of different wheelbases were offered

from the third series onwards. The Astura became a favourite

of the coachbuilders and many different versions were built

by almost all of the leading names. Around 5500 Artenas and

2900 Asturas were built in production runs which lasted

throughout the 1930s.

Nevertheless,

despite the relative success of these models, the poor

economic situation in Italy was a persistent worry and the

idea of a Lancia to tempt upwardly mobile Fiat drivers,

pitched between the Fiat Ballila and the Isotta, had been

playing on the mind of Vincenzo for quite a while. In 1930,

development had begun on the new model 231, the ‘Augusta’.

The first

‘compact’ Lancia designed to be produced in large volumes,

the Augusta was first shown to the public in 1932, with

production beginning in 1933 and a chassis version also

produced for the coachbuilders from 1934 onwards. For all

that, however, it was not a car for your average Italian,

and sold only a fraction of the amount of Ballilas in a

production run lasting between 1933 and 1937. If nothing

else, the quality of the car’s construction put it in a

different league – Trow describes how it came to be thought

of my many motorists as a ‘little Rolls-Royce’.

The

small-capacity engine, meanwhile, was a marvel of sorts in

itself. Under the direction of Gianni Sola, a brand-new,

1196cc, overhead-cam 18° V4 – with an unusual weight-saving

crankcase design – was developed, producing 35 bhp at 4000

rpm. It also possessed, says Paul Vellacott, “(a)

preciseness and delicacy (to) its controls, (especially) the

steering”; this was combined with sliding pillar independent

front suspension (providing excellent handling) and Lockheed

hydraulic brakes, although this latter innovation was fitted

only after much urging from Falchetto, and was not approved

without a great deal of reluctance from Lancia following

some problems in testing.

Despite its

diminutive size, this car was a particular favourite with

racing drivers of the era, with Tazio Nuvolari, Luigi

Fagioli, Antonio Brivio, Achille Varzi and Rene Dreyfus all

espousing the qualities of the ‘littlest Lancia’. With some

specialists also carrying out supercharger conversions, the

Augusta also met with considerable motorsport success in

private hands, from the Mille Miglia to the RAC Rally, with

their most notable success a 1-2-3-4 class finish in the

1936 Targa Florio.

Altogether, the

Augusta is perhaps best summed up by L.J.K. Setright, who

wrote that it represented, “perhaps the first really

successful embodiment of an ideal that many manufacturers

had long sought: an elegant, attractive, efficient and

completely convincing good small car. Too often dismissed as

merely pleasant, the Augusta – as a transitional design

paving the way for the Aprilia – was truly important.” Why

was this? Most importantly from a chassis design point of

view, the Augusta marked a return to a true load-bearing

bodyshell, with even the roof an integral part of the

structure. The chassis was also notable for being ‘pillarless’,

with the B-pillars being omitted, allowing for outstanding

access. This, it might be expected, did little for chassis

rigidity, but in fact, thanks to ingenious design, body

rigidity was quite superb. Despite weighing just 818kg,

according to Setright, the Augusta’s chassis boasted a

torsional stiffness of 4520lb ft per degree – an outstanding

figure, “unrivalled by any racing car for at least another

twenty years and unmatched by many a minor hatchback (well

into the 1990s).”

With such

thoroughness exemplified throughout its design, the Augusta

proved a success, to the point that Lancia set up a

brand-new factory in Bonneuil-sur-Marne, in France. Between

1933 and 1937, around 2500 Augustas, renamed ‘Belna’, were

produced at this factory, while a further 600 chassis were

destined for French coachbuilders such as Franay, Figoni and

Saoutcick. Including Italian manufacture, approximately

20,000 saloons and chassis were produced in total.

By 1934,

although the Augusta, Artena, Astura and Dilambda were all

rolling off the production lines at a steady rate, Lancia’s

thoughts were already turning to his next step, “a quality

car built on mass-production lines.” The car which

resulted, the Aprilia, would continue to forge the company’s

reputation for innovation, and carve out a wonderful

reputation for its quality, spaciousness, performance and

dynamic ability.

As with the

Lambda, so with the Aprilia: way ahead of their time is an

apt description for both. Like its predecessor, it boasted

unitary construction and an overhead-cam alloy-block V4, but

it differed in the nature of its advancement. As Paul

Vellacott has observed, if the Lambda was, “a remarkably

intuitive leap in to the future, the Aprilia was more of a

considered step into the future of the motor car...(the

result of) the confidence of a further fifteen years design

experience.” Falchetto remained the chief designer, but

responsibility for engine design passed from Ingegnere Rocco

to Ingegneres Sola and Verga, with the whole operation

overseen by the company’s technical manager, Giuseppe Baggi. In

fact, this was more significant than it may appear, for

Lancia’s role as principal of the company meant he simply

could not devote the time to become involved in the car’s

development, and his direct involvement ran only to laying

down its specification, although he kept a constant eye on

its development throughout the process. This was to include

a medium-capacity engine producing around 50 bhp; space to

carry five passengers; a weight, when laden, of no more than

900kg; good aerodynamic qualities; excellent roadholding;

and possibly, if the development team saw fit,

all-independent suspension.

This last

stipulation was realised, and the result was the first

Lancia to feature fully independent suspension, a feature

still unusual at the time. As with all Lancias since the

Lambda, the front suspension was again of sliding pillar

type, but the rear was an advanced and complicated trailing

arm/torsion bar arrangement at the rear, as opposed to the

inferior swing-axle designs of many of its

contemporaries. Other noteworthy features included hydraulic

brakes (inboard at the rear) and ‘pillarless’ aerodynamic

bodywork (Cd 0.47, versus an average for the time of

0.60). This was partially shaped in the windtunnel at Turin

Polytechnic by Falchetto, with the help of Pinin Farina,

making it one of the first mass-produced cars to ‘recognise’

aerodynamics, although Lancia himself insisted on a less

radical aesthetic treatment for the tail than the ideal

solution suggested by the tests. Lightness and rigidity were

also priorities, in order to fully exploit the benefits of

independent suspension, and clever construction allowed

torsional rigidity to be improved by no less than 20 percent

over the already impressive Augusta.

On the engine

side, Sola and Verga came up with another new narrow-angle

engine, this time a 1352cc 18° V4 (which would, much later,

provide the inspiration for Volkswagen’s famous ‘VR6’

engine). This was enhanced with the use of valves

positioned at 45°, duralumin conrods, and one of the first

production applications of a cross-flow head and

hemispherical combustion chambers. Furthermore, its

spaciousness was a revelation compared with equivalent cars,

whilst its performance and handling were to a standard more

commonly associated with many sportscars of the day. Lancia

himself experienced the car for the first time on a round

trip from Turin to Bologna, at the conclusion of which he

remarked, “Che macchina meravigliosa!” What a magnificent

machine! It was a deserved accolade – even today, the

Aprilia is employed as a textbook demonstration of applied

aerodynamics, intelligent packaging and excellent

performance.

Tragically,

Vincenzo would not live to see his creation go into

production and receive the plaudits it richly deserved. It

was, perhaps, the strain of running what had become a large

organisation which was taking its toll. In the early hours

of February 15, 1937, Lancia awoke in distress, but the

discomfort was minor enough for him to think nothing of it

and avoid disturbing his wife or staff. It was not until

seven o’clock in the morning that the family doctor was sent

for, who came as quick as he could, but by then, tragically,

it was too late. Thus, one of the men who had contributed so

much to the history of motoring had unexpectedly died at the

age of 55, the victim of a heart attack. His work as a

manufacturer was marked by intuition, originality,

nonconformity and courage. Equally, it is no accident that

his spiritual legacy is a car: the Aprilia. The model, which

seems to sum up the traditions of the company and the

virtues of the man, was initially received with scepticism

and a certain degree of incredulity – the design seemed too

daring, the technical aspects too innovative. It took some

time for this Lancia to become the queen of the road:

dynamic, extremely stable, with an incredibly modern style

appreciated by all. And it was the genius of Vincenzo Lancia

that foresaw it all.

It is for his

masterpieces, the Lambda and Aprilia, that Vincenzo will be

best remembered. But as Nigel Trow notes, to allow his

reputation to rest solely on the innovations displayed in

these two cars, “is to neglect the overriding character of

all Lancia cars – their quality of understated elegance. Not

elegance in the external, decorative sense but elegance as a

nicely judged solution to given problems, resulting in

engineering as art. Lancia was not concerned with novelty,

only with the pursuit of his own personal view of the motor

car, and his real brilliance lay in an ability to weld

together a number of individually exciting ideas into a

workable whole. Underpinning this genius lay a sense of

proportion which made Lancia cars the most utterly human

vehicles ever made.” Similarly, on the philosophy of Lancia

cars, one imbued by Vincenzo himself, L.J.K. Setright

observed that, “nothing is given special emphasis, just as

nothing is dismissed as unimportant; the whole thing is a

balanced design, and it is that equilibrium which – ignoring

all temptations to exaggerate any particular aspect of its

character – has always been typical of Lancia. (Considering)

the car as a whole, rather than engaging in blinkered

pursuit of some isolated idiosyncracy, is what has made

every Lancia good and no Lancia spectacular”, and this

holistic approach is reflective of the philosophy of the

company’s founder. Although the company was never quite the

same after his passing, Vincenzo’s unique approach would

continue to imbue Lancia’s products well after his death,

even though persistent financial troubles would plague the

company over the next few decades.

by Shant Fabricatorian

|

|

|

|

![]()

![]()