|

Lancia, one

of the most famous and evocative of all the major automotive

brand names, was founded exactly 100 years ago. To

celebrate this milestone Italiaspeed is presenting an

exclusive 15 part history of Lancia.

Having recently

launched the revolutionary Aprilia, Lancia entered a new era

in 1938, with the arrival in Turin of the legendary Vittorio

Jano, responsible for the highly-regarded and tremendously

successful Alfa Romeo P2, 1750, 2300, 2900 and P3. Jano had

been sacked from Alfa Romeo the previous autumn, most

believe unfairly, for the failings of the latest Tipo 12C/37

chassis; Alfa’s loss was Lancia’s gain, as he accepted an

invitation to become the company’s technical director.

Jano’s first

project on his arrival at Via Monginevro was of a somewhat

different nature to what he was used. With the Aprilia on

the market, attention had turned to the little Ardea, the

smallest Lancia ever made, introduced as a new upmarket

utility model to replace the Augusta just prior to the

outbreak of hostilities in 1939. Following the style of the

Aprilia, the external design was in fact closer to the shape

which Vincenzo had rejected as too radical for the Aprilia.

Indeed, despite a wheelbase a full foot shorter than the

Aprilia (at 8ft), it had almost as much space inside.

Furthermore, the

Ardea’s concept of a narrow-angle OHC V4 engine and

sliding-pillar independent front suspension also displayed

similarities with its bigger brother. The overall technical

solutions employed, though, were rather simpler, especially

the rear suspension (live axle on semi-elliptic leaf

springs), outboard hydraulic brakes, and the lack of an

opening boot for luggage, while fuel was gravity-fed from a

tank under the bonnet. Second series cars introduced a 12V

(rather than 6V) electrical system and opening bootlid,

although the ongoing conflict meant that production had

slowed to a trickle throughout the war years. Later

improvements in the fourth series also saw the use of

aluminium alloy for the cylinder head, higher compression

ratio and an accompanying boost in power, from 28.5 to 30

bhp, whilst the third series, produced from 1948, debuted a

five-speed gearbox (actually an overdrive) – a world first

on a production car.

In fact, this

feature unintentionally caused some consternation at the

time. As Paul Vellacott tells the story, when Juan-Manuel

Fangio saw his Ardea, he said, “I was very sorry to have to

sell my Ardea when I started to drive for Alfa Romeo, it was

such a clever little car.” Having placed an advertisement

for it, a lady had responded, buying the car after Fangio

had taken her for a short demonstration drive. However, she had

returned a couple of days later, claiming something had gone

wrong with it – it was now much slower than when Fangio had

demonstrated it to her. Fangio thus took her out for

another run and the car again attained the 106 km/h it had

reached the first time. This satisfied the lady, but a day

later she returned, resolute in her avowal that the car

would definitely go no faster than 93 km/h. It was, of

course, only then that the penny dropped – Fangio had

neglected to point out that the car had a fifth gear...

Despite the lack

of a commercially-available chassis for the coachbuilders

(one was developed but never put into production), a few

variants of the Ardea were built, by Zagato and Pinin Farina

amongst others. The model was also noteworthy for being

built in commercial variants in considerable numbers: as a

taxi, a small truck (camioncino) and a van (furgoncino). A

total of around 22,000 vehicles were produced.

The Ardea would

be replaced as Lancia’s entry-level model by the 1953 Appia,

once again overseen by Jano. Stylistically, it was another

pillarless four-door saloon which echoed the company’s

flagship model, in this case the recently-launched

Aurelia. As with the Ardea, however, its specification was

more utilitarian, with a live axle with leaf springs and

telescopic dampers at the rear, a conventional column-change

four-speed gearbox, and outboard rear brakes. For all that,

it retained many Lancia engineering hallmarks: the standard

layout of front sliding pillar suspension (the last model to

feature it); aluminium doors, boot, bonnet and rear wings to

save weight; and a new, Jano-designed, 1090cc V4

engine. With a V-angle of 10°, this was the narrowest and

shortest V4 yet, a feat made possible by developments in

petrol and metallurgy during the war. L.J.K. Setright notes

that it was somewhat taller than ideal, and in this respect,

“Jano’s substitution of pushrod valve actuation for the

traditional Lancia overhead camshaft did not actually help

(it was primarily chosen for reasons of economy); but by

really neat cylinder staggering he saw how to shorten the

crankshaft so much that it could dispense with central

support and run happily in two main bearings.”

In 1956 the

second series was introduced. This had a noticeably

different external aesthetic, with a more pronounced boot

and more vertical rear window resulting in a ‘notchback’

style. The wheelbase was also extended by 30mm and power was

increased from 38 to 43.5 bhp with the introduction of

hemispherical combustion chambers and a more aggressive

camshaft profile, whilst inside, the individual front seats

were replaced by a single bench seat.

This series also

formed the basis for many coachbuilt Appias. Coachbuilders

as diverse as Lombardi, Scioneri (saloons), Farina (coupe),

Viotti (estate and coupe) and Vignale (who in addition to a

saloon, produced an angular convertible from 1957) all

produced variations on the Appia, but perhaps the best-known

are the efforts of Zagato. The first was a one-off shown at

the 1956 Turin Motorshow (and known as ‘the camel’), which

also competed in the Mille Miglia the following

year.

Production models using the standard wheelbase were

the alloy-bodied GTZ (from 1957, with 53 bhp), and the GTE

(for ‘export’), which ran from 1958 and saw power increased

to 60 bhp. A short-wheelbase (2350mm) ‘Sport’ was also

offered, with the higher-output engine. All three cars had

different body styles and were built in small numbers (a few

dozen GTZs, 521 GTEs and 200 Sports). These were in addition

to the three other body variants also produced by Lancia:

the ‘furgoncino’ (small van), camioncino (pick-up truck) and

the autolettiga (ambulance). By the time production of the

Appia ceased in April 1963, well over 100,000 units

(including coachbuilt examples) had been produced, making it

the first Lancia to hit this sales mark and easily their

best-selling model to date, providing a vital source of

revenue at a difficult time for the firm.

However, this is

to rush the story. The war had proven an extremely

challenging experience for the firm, following on so soon

from the death of Vincenzo. With car production coming to a

virtual standstill, the factory found itself manufacturing

vehicles for the military, including investigations into

electric trucks (to cope with the shortage of fuel; two

hundred were built) and an all-terrain fighting vehicle

dubbed the ‘Autoblindata tipo Lince’ (Lynx), which had

four-wheel drive, four-wheel steering and fully independent

suspension (later copied by the Allies and developed into

the Ferret). The company suffered severely when much of its

plants and equipment were destroyed during the heavy bombing

of northern Italy in the autumn of 1942.

These challenges

were hardly allayed by a strategic decision which nearly

bankrupted the company. Immediately after the war ended,

management decided to concentrate on the production of

trucks, reasoning that transport would be in great demand.

What they did not count on was A.R.A.R., the public

organisation set up to sell the war surplus, unleashing 8000

trucks on the Italian market in 1948 at virtually fire-sale

prices. The resulting decimation of Lancia’s truck sales

came at a particularly stressful time for the company, which

was battling high indebtedness and a lack of new products.

However, as it

is said that fortune favours the brave, so Lancia took a

deep breath and committed itself to emerging stronger from

this crisis. It was in that same year, with the appointment

of Gianni Lancia as general manager, that the company

reacquired a leader able to oversee the design and

development of a new generation of models. The company

founder’s son was well aware of the need to revive company

traditions, but equally aware of the need to forge a

distinct reputation of his own. As Trow observes, “(Gianni)

knew well that his inherited reputation rested upon

excellent technical innovation and the satisfaction of

market needs.”

Although the

Aprilia would remain in production until 1949, the story of

its replacement may be traced back to seven years

previously, when engineer Francesco de Virgilio – an expert

in the difficult issue of finding the correct balance for V6

engines – had been charged by Lancia to investigate the

possibility of a crankshaft suitable for a 40° V6, created

by lopping two cylinders off a prototype V8 engine in the

Padua workshop. Lancia had in fact built a prototype

narrow-angle 2.6-litre V6 as early as 1924, which had been

installed in a Lambda, and various experiments with the

configuration had continued throughout the intervening

years. All of these had been shelved as other developments

were deemed more important, but in typical fashion, when its

time came around, Lancia’s first production V6 was a

thoroughly considered and tested entity.

At the end of

the war, the intent of the factory was to further develop

the Aprilia theme, perhaps with a new type of engine

design. V6s were appealing for their attractive potential

power outputs compared with a four-cylinder, but as yet

no-one had been able to overcome the horrific vibration

problems inherent in such a layout. To this end, de Virgilio

wasted little time in designing a new prototype 1569cc V6

engine with a V-angle of 45°, the maximum which would fit

under the Aprilia’s bonnet. After several thousand

kilometres of testing underneath an Aprilia bonnet

throughout 1947, this evolution of the Aprilia was cancelled

by Gianni Lancia the following year, in favour of an all-new

model. Following a further prototype of the same capacity

but with the V-angle increased to 50°, de Virgilio

eventually concluded that the only satisfactory solution was

to increase the V-angle up to the optimal value of 60° – the

figure which would be adopted for the new production engine.

Well aware of

the company’s need to uphold its reputation for technical

innovation, Gianni had stipulated the requirements for the

Aprilia’s replacement as follows: it must have six

comfortable seats, be equipped with a 1.5-litre, 60° V6,

have highly aerodynamically efficient unitary construction,

and weigh less than 1100kg. The typical buyer of the Aprilia

had been, in the words of Riccardo Felicioli, a true ‘Lancisti’. He

defines this as the following: “a keen motorist who paid

careful attention to the vehicle’s real value and its

technical substance; he was able to understand and

appreciate the originality and subtlety of the most daring

and sophisticated technical solutions: in short, he was an

authentic connoisseur.”

On every count,

the Aprilia’s successor did not disappoint such Lancisti.

Launched at the Turin Motorshow on March 4, 1950, the

Aurelia was new from the wheels up, with its outstanding

technical highlight undoubtedly the world’s first production

V6, a feature which has guaranteed this model a hallowed

place in the annals of motoring. Designed by de

Virgilio, in collaboration with Ettore Zaccone Mina, the

final result was, and remains, a beautiful piece of

engineering in its own right – an all-alloy unit with

hemispherical combustion chambers, displacing 1.8 litres

(1754cc) in its initial form. Valve actuation was via

pushrods, driven by a single camshaft located in the centre

of the ‘V’. The heads were kept narrow by splaying the

valves at an angle relative to the length of the head,

rather than its width, while other interesting features

included wet cylinder liners, a cam-chain tensioning device

activated by oil pressure, and auxiliary oil pumps placed

within both the gearbox and the rear axle.

To concentrate

solely on the new engine, however, would be to ignore a

number of other extremely important technical developments

which appeared on the Aurelia. It was, for example, the

first car to have Michelin’s revolutionary ‘X’ radial tyres

as original equipment (continuing a long relationship

between the factory and the French tyre company), while

other prominent technical points included independent rear

suspension by semi-trailing arms and coil springs, transaxle

layout (with synchromesh on all four gears), hydraulic

brakes (inboard at the rear), and extensive use of aluminium

(including the doors, bonnet and bootlid), which kept the

weight down to an impressive 1080kg. Especially in the use

of a transaxle and independent rear suspension, the new car

bore Jano’s distinct imprint. Front suspension was by

traditional Lancia patented sliding pillar, with the shock

absorber incorporated within the coil

spring.

The first year

saw production of the Aurelia B10 berlina, a four-door

pillarless saloon with the 1.8-litre engine, producing 56

bhp. Answering some criticism of the car’s performance, the

following year saw the introduction of the B21, which had an

uprated 2.0-litre (1991cc) engine producing 70 bhp. A

six-light limousine, the B15, was also derived from the B21

and built in small numbers by Bertone. This version had the

wheelbase extended by nearly 200mm and the engine detuned to

65 bhp.

|

|

|

Further developments to the Aurelia B20 resulted in

a third series entering production by 1952, often

referred to as the ‘GT 2500’. |

|

|

|

At

the end of the war, the intent of the factory was to

further develop the Aprilia theme, perhaps with a

new type of engine design. Above: 1946 Aprilia Sport (Pagani Barchetta Corsa). |

|

|

|

By

the time production of the Appia ceased in April 1963, well over 100,000 units

(including coachbuilt examples) had been produced, making it

the first Lancia to hit this sales mark and easily their

best-selling model to date, providing a vital source of

revenue at a difficult time for the firm. |

|

|

|

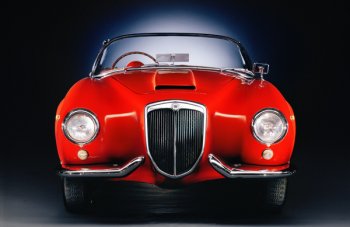

For the motorist looking for the ultimate in refined

elegance, sportiness and glamour in the 1950s, it

was difficult to go past the Aurelia B24 Spider,

first seen as a prototype in 1954 but officially

introduced during the 1955 Brussels Motor Show. |

|

|

|

|

Having recently

launched the revolutionary Aprilia (above), Lancia entered a new era

in 1938, with the arrival in Turin of the legendary Vittorio

Jano, responsible for the highly-regarded and tremendously

successful Alfa Romeo P2, 1750, 2300, 2900 and P3. |

|

|

|

Jano’s first project on

his arrival at Via Monginevro was the Augusta’s

replacement, the Ardea, introduced as a new upmarket

utility model just prior to the outbreak of war in

1939. |

|

|

|

Launched at the Turin Motorshow on March 4, 1950, the

Aurelia was new from the wheels up, with its outstanding

technical highlight undoubtedly the world’s first production

V6, a feature which has guaranteed this model a hallowed

place in the annals of motoring. |

|

|

|

The Ardea would

be replaced as Lancia’s entry-level model by the 1953 Appia

(above),

once again overseen by Jano. Stylistically, it was another

pillarless four-door saloon which echoed the company’s

flagship model, in this case the recently-launched

Aurelia. |

|

|

|

Boneschi, Vignale, Allemano, Stabilimenti Farina and Ghia,

used a special extended chassis series of the Aurelia, created by the factory, as a basis for their work, with perhaps

the most striking vehicle to emerge from these efforts a

futuristic concept car by Pinin Farina, the 1953 PF2000

(above).

|

|

|

|

By

1955, the situation had deteriorated to the point that

Gianni Lancia and his mother were forced to sell the

family’s majority holding in the company to industrial

conglomerate Italcementi, headed by millionaire Carlo

Pesenti.

|

|

|

The berlina

received another boost in 1952 when the B22 was

released. Notwithstanding minor changes such as the

instruments and indicators, this was essentially a B21 with

a modified camshaft and a twin-choke Weber carburettor,

which helped boost power to 90 bhp. This variant continued

until 1954, when the arrival of the B12 heralded significant

changes to the Aurelia.

The most

important revision arising from this ‘second series’ was the

adoption of a de Dion suspension layout on leaf springs at

the rear, in place of the previous fully-independent setup,

which helped keep camber change in check under cornering

load and made wet-weather handling in particular more

predictable. Further modifications included the replacement

of the white-metal bearings with Vandervell items, a new

cartridge oil filter, and a new block casting. With a 2266cc

engine and 87 bhp, the B12 also incorporated numerous other

small detail changes to the design, such as the headlights,

spotlights, and wind deflectors on the windows.

Additionally,

Lancia had released a chassis with an extended wheelbase

alongside the debut of the standard car in 1950,

specifically designed for the use of the various carrozzerie. This was designated the B50, or B51 with different gear

ratios and tyres; later becoming the B52 and B53

respectively with the adoption of the 2-litre engine. A

small number of chassis with de Dion rear suspension were

also produced (B55 and B56), as well as a single B60.

Various carrozzerie, including Pinin Farina, Bertone, Viotti,

Boneschi, Vignale, Allemano, Stabilimenti Farina and Ghia,

used these chassis as a basis for their work, with perhaps

the most striking vehicle to emerge from all these efforts

being a

futuristic concept car by Pinin Farina, the 1953 PF2000.

Nonetheless, as

beautiful and striking as some of these coachbuilt cars may

have been, they were arguably overshadowed by Lancia’s own

efforts with their coupe derivative of the Aurelia, the

‘Gran Turismo’, more popularly known as the B20 GT. Once

described as, “a grand tourer which would have made the late

Vincenzo Lancia smile”, the B20 GT remains one of the most

famous Lancias ever, as well as one of the all-time great

automobiles. Built on a wheelbase some 200mm shorter than

that of the saloon, the B20 defined the modern template for

the Gran Turismo, or GT.

Although the first use of

the term was on the Alfa Romeo 6C 1750 Gran Turismo, it was

the Aurelia which popularised it and helped make ‘Gran

Turismo’ a concept in its own right. Robert Coucher

observes that, “as a Gran Turismo, the Aurelia is

superb. It’s light and minimal in construction but not

fragile like Alfa Romeos of the same era: the result of

functional weight-paring, not cost-cutting with

insubstantial components. Beneath its skin, the mechanicals

are rugged and well conceived, allowing rapid progress on

challenging roads.” At substantially more than the price of

a Jaguar D-Type in the UK, it was far from cheap, but for

those who could afford it, it offered a sublime blend of

quality, styling, performance, and dynamic integrity. It is

no surprise to find that it was extremely popular with many

racing drivers of the day, including Jean Behra, Mike

Hawthorn and Juan-Manuel Fangio.

Although the

handsome full-width bodywork of the B20 is sometimes

attributed to Pinin Farina, who tidied up the design before

its debut, it is commonly felt to largely be the work of

Ghia’s Mario Felice Boano, who amongst other projects is

noted for his work on the Alfa Romeo Giulietta Sprint. It

was only limited production capacity which prevented Ghia

from building the cars as well; the first 98 examples

produced are ascribed to Carrozzeria Viotti, while

increasing demand thereafter resulted in a shift to Pinin

Farina’s works (Lancia supplied a rolling platform to the

coachbuilder, to which hand-beaten panels were welded).

Mechanically, it was broadly as per the B21, with a slightly

tuned engine producing 75 bhp. Soon afterwards, after 500

S1 cars had been produced, production began of the second

series coupe, which used an 80 bhp version of the same

engine (the improvement obtained through repositioned valves

and a higher compression ratio). Additionally, the brakes

were improved, the ride height reduced, and a few detail

styling changes made to things such as the instrumentation

and chrome trim.

Further

developments to the B20 resulted in a third series entering

production by 1952, which was often referred to as the ‘GT

2500’. Along with some mild alterations to the styling

(especially in the profile of the tail), the V6’s capacity

was expanded to 2451cc, now developing 118 bhp. This

increase in power began to show up some weaknesses in the

suspension design, so the fourth series introduced a de Dion

layout at the rear to replace the previously independent

system in 1954, along with the possibility to buy a

left-hand drive version for the first time. Subsequent B20

models

became more biased towards luxury with somewhat superfluous

additions: the fifth series in 1956 (which added a direct

drive top gear) was heavier and had a softer cam profile for

increased torque, and with power reduced to only 110 bhp, while

the sixth and final series (1957 on) added even more weight

(a total increase of over 1000lb over the S1), not

completely offset by a minor increase in power to 112 bhp.

For the motorist

looking for the ultimate in refined elegance, sportiness and

glamour, however, it was difficult to go past the Aurelia

B24 Spider, first seen as a prototype in 1954 but officially

introduced during the 1955 Brussels Motor Show. The B24’s

bodywork was both designed and built by Pinin Farina, and it

is widely considered to be one of the coachbuilder’s most

successful designs; elements deriving from it would later

pop up in designs such as the Alfa Romeo Giulietta Spider

and Ferrari 250 GT California. Based on a fourth series B20

chassis shortened by a further 210mm, the Spider was fitted

with the latest mechanical specification from the coupe,

which meant the 2.5-litre engine and de Dion rear end, and

floor-mounted gearlevers on certain left-hand drive cars.

Only 240

examples of the Spider were produced until 1956, when it

gave way to the GT 2500 Convertible (aka

‘America’). Featuring a completely redesigned body, the

Convertible had no panels common to the Spider; the latter’s

wrap-around windscreen was ditched in favour of a flatter

windscreen with small quarterlight panels, along with deeper

doors (incorporating door handles) and one-piece straight

bumpers. The aim was to make the car more comfortable and

user-friendly, and in that aim Lancia was successful; but it

is also generally agreed that a deal of the Spider’s purity

and delicacy was sacrificed in the process.

Like the B20,

production of the Aurelia Convertible ran until 1958,

whereas production of the berlina wound up a couple of years

prior. For all its charms, significance and timeless design,

the Aurelia failed to sell in sufficient numbers to be

viable, with just over 18,000 examples of all models leaving

the factory gates over eight years (broken down into 12,786

saloons, 3871 coupes, 761 Spiders/Convertibles and 778 bare

chassis). By 1955, the situation had deteriorated to the

point that Gianni Lancia and his mother were forced to sell

the family’s majority holding in the company to industrial

conglomerate Italcementi, headed by millionaire Carlo

Pesenti.

The reasons for

the financial crisis are complex and disputed, but it is

likely that a number stem from the particular technical and

organisational culture which characterised the company from

the off. Although the Aurelia’s lack of viability placed the

company close to the financial precipice, and the huge

expense of the competition programme was the trigger for the

family’s loss of control, Giuseppe Berta is careful not to

underestimate the significance of the company’s lack of

responsiveness to developments outside the technical

arena: “Lancia’s corporate system was, in the early 1950s...a

mixture of contradictions. It produced models like the

Aurelia which overwhelmed the market, whilst its

technological and organisational modernisation was at a

standstill. It continued to pursue an ideal aspiration for

technical excellence...when in practice it had abdicated

from all entrepreneurial and managerial-type behaviour.

“(Within Lancia

during this period,) the technical control and disciplinary

authority of the company were at an all-time low, whereas

the discretionary power of the workers was extremely

high. In fact, workers, technicians and management all

shared a single mentality...the outstanding importance

attributed to the technical quality of the product and the

attention paid to some executive phases were factors that

could quite easily stand alone from an exact understanding

of the lacunae in terms of efficiency and

costing.” According to Wim Oude Weernink, under Gianni’s

leadership there had been too heavy a concentration on the

technical aspects of the Aurelia project, as well as too

much effort and expenditure on different styles and

technical variations, at the cost of sufficient investment

in plant equipment which had been ageing since the end of

the 1940s. Reinvestment in the best machine tools available,

along with the building of the Lancia skyscraper on the Via

Vincenzo Lancia, was simply not being sufficiently repaid by

the weekly output of under 180 cars. In short, he says,

“Lancia was dominated by a technical and engineering

culture, exclusively concentrated on the project, and it was

this that finally inveigled the company to embark on the

extremely costly adventure of racing.”

Unfortunately

for Gianni, the racing programme would have a negligible

impact in improving the company’s sales. If nothing else,

however, it would bring fame to the company, establishing

the Lancia name in motor racing in some style, and provide a

suitable arena where the Aurelia’s outstanding handling and

performance characteristics could be put on show. The

sensational debut of a B20 GT on the 1951 Mille Miglia,

where it finished second overall, marked the beginning of

the factory’s steadily increasing commitment to motor racing

– a commitment which would ultimately culminate in Lancia’s

first and only Formula 1 car, and the adoption of the famed

‘running elephant’ logo to designate Lancia competition

cars. Between 1951 and 1955, the Aurelia and the specialist

racing cars which followed it would achieve a great number

of successes, going head-to-head against the likes of Alfa

Romeo and Ferrari.

by Shant Fabricatorian

|

|

|

|

![]()

![]()